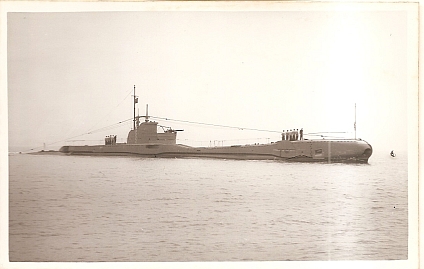

HM Submarine Triumph's last patrol - December 1941HM Submarine Triumph's last patrol - December 1941

Summer 1941 in Cairo. 8,000 Commonwealth soldiers trapped in southern Greece had surrendered at Kalamata. Perhaps another 1,000 evaded capture (or escaped soon after) and disappeared into the hills. In Cairo the local head of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) was trying to establish what SOE should be doing about sabotage and sedition in Greece. The problem was acute. SOE had no “stay behind” people in Greece. Some weapons and explosives had been left behind, but no-one knew where they had ended up. MI6’s people in Greece had all been blown or captured. Greece’s political scene was highly fractured and contentious. Royalists supported the return of an absolute monarch (at that time licking his wounds in Cairo). Liberal democratic Venizelists wanted a moderately right wing constitutional monarchy and democratic government. Republicans wanted a democracy without the king. Two varieties of communists were working towards a dictatorship of the proletariat. Metaxans supported the deposed dictator Metaxas. Each group hated the others, and personal loyalties were by no means clear. In Athens and elsewhere resistance cells were springing up (Ali Baba, Prometheus, 5-16-5, the Kyrou Group, the Zannas Group. In January 1942 an SOE memo referred to 22 known cells). People were sometimes members of more than one cell. Envoys and messengers were turning up in Cairo (having travelled across the Aegean to Turkey) bringing appeals for cash, weapons, radios and training. The Royalists in Cairo were scheming to get HMG to endorse the return of the king after the war, while the Foreign Office was trying to work out what it wanted and who it should therefore support. And all the while SOE in London was demanding action. Atkinson had been captured at Kalamata and was being held in a transit camp near Piraeus. The camp had been thrown up in a hurry, and was not secure. Atkinson escaped one night, and headed to Athens to try and find the Underground. By a series of chances he happened on the Bouboura sisters, who took him to the Ioannou family, living in Patission Street. The Iouannous were prosperous tobacco merchants with an import business in London, so were good English speakers, and had the space to hide Atkinson and the New Zealander Ted Cooper. The daughter of the household was Efi Ioannou, aged 15, who now lives in London, and who remembers Atkinson well. "we called him Mac, for some reason. The house was crowded, with our parents, us three children, our English nanny Miss Morris, two servants and two Allied soldiers. Food was in short supply, and we had to live by buying food on the black market". Atkinson spent a couple of months in Patission Street. He occasionally went out - on one memorable occasion sitting on a park bench next to a German soldier - but eventually arrangements were made to take him and other escapers to Alexandria, where he turned up in October 1941. Allied soldiers who had managed to evade capture, or escape, were trickling into Athens in and other Greek cities in dozens looking for shelter, and help in getting back to Egypt. This was willingly offered by Greek patriots, but in turn led to heartfelt pleas to Cairo for money and transport.

Efi Ioannou, now Kulukundis, in London In Cairo MI9, the escape and evasion organisation, was struggling with the same problems as SOE – who to trust, how to communicate, how to get resources into Greece, and how to get people out. SOE and MI9 were in essence competing for the same resources, and were far from friends. A key problem was transport – how could people and supplies be got into and out of Greece? The Greeks themselves supplied the early answer – small coasting vessels called caiques were capable of making the 500 mile crossing from Alexandria to the Aegean, and the much easier crossing from the mainland of Greece to the coast of neutral Turkey only a hundred miles to the East. Almost as soon as Greece fell a trickle of caiques and travellers began to arrive in Alexandria by these two routes. Return to Greece was more problematic. The German and Italian authorities kept track of caique movements, and an absence of more than three days was enough to brand a caique and its captain as Allied collaborators. Hence, once a caique arrived in Alexandria it could not return openly to Greece. A caique could pick people up in Turkey, if they could be got there covertly (the Turks were neutral, but basically hostile to the Allies), but inbound travellers would first have to travel by land from Cairo, and then take their chances on the arrival of a suitable smuggler. In theory supplies could be parachuted into Greece, but in practice this wasn’t attempted until a year or more later, and problems with aerial navigation by night made parachute drops a more miss than hit affair. Which left submarine landings. The techniques of beach landings by submarine had been well established and practiced during 1941, and a boat could land three or four people in relative safety, along with supplies, radios, money and even weapons. The problem was that submarines were in short supply, and landing agents in Greece was a low priority compared with sinking Rommel’s supplies. A landing mission consumed about one tenth of the patrol time available to a boat. Some landings were being made in 1941, but only those with the highest priority. It was in this troubled environment that, on the 18th October 1941, a caique appeared in Alexandria, under the command of a Greek rogue and peacetime smuggler called Harry Grammatikakis. Among the soldiers aboard was Lt George Atkinson of the RASC. Atkinson was swiftly enfolded in the embrace of both MI9 and SOE, as a source of recent intelligence on what was happening in Greece, and as a possible volunteer to return and work for both SOE and MI9 in Athens. Both organisations quite reasonably surmised that Atkinson’s contacts would be useful, and that he would be seen as a trusted emissary. Atkinson was an enthusiastic volunteer, and took up residence in the flat of a senior SOE officer in Cairo while he was trained and prepared for his new job. He arranged for the BBC to transmit a message on the evening broadcast - to Efi Ioannou in Athens who, he knew, would be listening intently to her secret and highly illegal wireless in the attic of Patission Street. MI9’s chief in Cairo, Major (later Colonel) Tony Simonds, had a problem. Bringing evaders out by caique meant “burning” the caique and its crew every time, because the caique would have to breach its three day allowance. Apart from the inconvenience of losing caiques, MI9 also had to compensate their owners in hard cash, and cash was in short supply[3]. Evaders were dribbling into Smyrna in Turkey (one pair rowed across the Aegean), but there were many more hiding in and around Athens looking for a way to get home. The problem with using a submarine to pick up evaders was in coordinating evaders and a boat into the same place and time without any safe means of communicating with the evaders in Greece. Simonds’ problem was how to get enough evaders together to meet a boat to justify tasking a valuable submarine, while avoiding the risk that the enemy would discover the rendezvous and sink the boat, or worse, capture her. The problem was compounded by the fact that a boat could only pick up reasonable numbers of people at the end of her patrol. There were three reasons for this. First, the length of a patrol was already defined by the amount of food and water a boat could take to sea. Add 20 or 30 mouths to feed for more than a few days and the boat’s patrol endurance would be slashed. Second, the presence of many additional people aboard would endanger a boat because they would quite simply get in the way during an attack or an evasion. Finally, and probably crucially, a dived submarine had just enough breathable air to support her crew (57 for a T class) for about fifteen hours – allowing her to stay submerged during daylight with a margin at each end for evasion if she was attacked. Add 20 or 30 sets of lungs and her dived endurance would fall to about nine hours – forcing her to spend some time each day on the surface in daylight. The air situation in a submarine is graphically described by Antoni Banach, quoted in "The Fighting Tenth": "At dawn we would submerge, , and after the first four hours the air inside the submarine would gradually deteriorate and become noticeably stale. After about ten to twelve hours the temperature would be 27 Celsius, and breathing became more difficult.. At the time I was 22 and found it uncomfortable, but the older men found it more difficult. By the time eighteen hours had passed since submerging, some of the crew were having a hard time...the last few hours before surfacing were the worst for the older crew and the inexperienced, who would by now be gasping and struggling for every breath and perspiring heavily." Adding a couple of dozen people to the 57 already aboard would cut Trumph's dived endurance from 18 hours to 12. In the closely patrolled waters of the Aegean this would be tantamount to suicide. So, if a large party of evaders was to be picked up, it would have to be done at the very end of a patrol, at night, allowing the boat to make a good hundred miles of surfaced passage before diving in open water with almost no chance of detection. But how could 20 or 30 evaders be reliably and secretly assembled in one place for a submarine rendezvous? Grammatikakis seems to have suggested the answer - a small barely populated island in the centre of the Aegean called Antiparos. A quick look at Google Earth will show that Antiparos is almost designed for Simonds’ problem. The island could be reached in less than a day by caique from pretty much any part of mainland Greece, allowing the caique to return home in less than three days, and so avoid suspicion from the enemy. At the southwest end of Antiparos there is a perfectly sheltered sandy bay with a fine shelving bottom, and with good clear access to open water. Finally, the island has some houses, for shelter, but no Italian garrison. Best of all (and I suspect this is where the suggestion came from) Grammatikakis was having a relationship with a girl who lived on the island, so was a familiar face to the locals. By the end of October the decision was made. Antiparos would be established as a secret base in which to assemble and hide evaders. With evaders collected and waiting, a submarine could simply arrive whenever convenient, knowing that there would be a good number of evaders within 20 minutes’ walk to collect and take home. No advance rendezvous would be needed, so reducing the risk to the boat of being bounced by the enemy in mid-pickup. The base could be provisioned with food, fuel, clothing and a radio, and the time delay between an evader arriving and being picked up would give a chance that any German "plants” could be detected and dealt with[4]. The plan was set, and christened CONEY ISLAND, while the base itself was codenamed HARLEM. The first provisioning trip was made by HMS Thorn, leaving on 10 November 1941. A few days later Thorn dropped Atkinson, Grammatikakis and a Sergeant Redpath (a New Zealander) plus a radio on Antiparos. An arrangement was made for Thorn to return a fortnight later, and meanwhile Atkinson and Grammatikakis travelled to Athens by caique to round up evaders. Redpath made himself comfortable in the house of an islander called Tzavellas. The plan worked like clockwork. Around 28th November Thorn returned to Antiparos, and picked up Atkinson and 20 evaders (codenamed rather unkindly ELKS), returning to Alexandria on 30th November. Redpath and Grammatikakis stayed behind, the former to maintain the base, and the latter to return to Athens to round up more evaders. Back in Cairo SOE was anxious to get in on the act. A picture of the competing and confusing resistance cells was beginning to emerge. The most efficient and active seemed to be the two communist operations (which later merged), and these had been sent a radio set by an earlier landing party from Triumph. The set and its operator were codenamed 333. SOE knew it had to get sets and operators to each of the main parties in Greece, if it was to avoid the resistance being completely co-opted by the communists. It also needed to get money to its various cells, and to transmit its instructions for sabotage, subversion and assassination. At the same time it needed to clarify just who was working for and with who, and to understand what resources of people and equipment each cell could command. All of these tasks demanded an envoy, and of course a perfect candidate was sitting in the SOE flat in Cairo, in the form of Lt Atkinson. SOE knew, from chats over an evening whisky, that MI9 was planning a second supply and pickup mission to Antiparos/HARLEM for December. Simonds decided to ask Atkinson if he would undertake an SOE mission on the same trip – namely go to Athens, make contact with two of the cells (the Kanellopoulos Cell, led by Professor Panayiottis Kanellopoulos, whose code name was CUTHBERT, and the Zannas cell, led by Alexander Zannas), and hand over cash and bring a wireless operator with a set. Atkinson readily agreed, but with a suspicion that his MI9 employers might not be delighted at his moonlighting, asked SOE not to mention his SOE tasks to his MI9 colleagues. SOE nominated a Greek called Diamantes who they had been training in wireless operation. He was given the codename DIAMOND[5], And was ordered to act as wireless operator for CUTHBERT. A joint meeting with Captain Raw, commander of the First Submarine Flotilla, led to the mission being designated a joint MI9/SOE landing, and in SOE’s files the mission was codenamed ISINGLASS. Atkinson’s mission had become rather complicated. On his to-do list were the landing of three tonnes of supplies and two tonnes of fuel on Antiparos, a trip to Athens escorting DIAMOND, meetings with Zannas and Kanellopoulos, passing over of instructions and money, negotiations with Zannas and Kanellopoulos to try and persuade them to cooperate, rounding up of evaders in Athens, and then their covert transport back to Antiparos. While ISINGLASS was being planned SOE made a change in the way it ran its agents, and responsibility for Atkinson was passed to a new hand (codenamed DSO – I haven’t been able to find his actual name yet. DSO probably stands for Director of Special Operations). DSO was new to the game of agent handling, and did not notice the accumulation of risk that was building up in Atkinson’s orders. Compounding his error, DSO decided that Atkinson had so much to do that he needed a written operation order. This was duly prepared, and among other items contained a complete en clair list of all fourteen members of the Kanellopoulos cell known to SOE. Even though this op-order was prominently headed “NOT TO BE TAKEN ASHORE”, it was sadly to prove Atkinson’s death warrant, as we shall shortly see. While preparations were being made in Alexandria and Cairo, Grammatikakis had travelled to Athens and by 10th December 1941 had managed to get 18 evaders to HARLEM (by the skin of his teeth, as the Germans got wind of the move and narrowly missed capturing the whole party south of Athens). He returned to Athens to pick up food (no easy task given that the Germans were now actively starving Greece to death. Greek history narrates that 400,000 Greeks died of starvation during the occupation, some tenth of the population), and fuel, in case he needed to take the evaders to Alexandria himself. In Alexandria, Triumph had come back from patrol on 11 December, to the welcome news that this was her last patrol. Her next trip would be across the Mediterranean to Gibraltar, and then home for leave and a refit. The news was premature. ISINGLASS needed a boat, and Triumph was the only operational boat available. She was given the job. Triumph spent Christmas day alongside in Alexandria, doubtless a kindness to a tired ships company from Captain Raw, and slipped her moorings on the afternoon of boxing day, with Atkinson, DIAMOND, and an experienced liaison officer, Captain Craig, aboard. Craig was another New Zealander who had made a number of trips back into occupied Greexe. Also aboard were five tonnes of stores for HARLEM[6]. It is here that the Staff History and our history diverge. Followers of this story will recall that all UK sources agree that Triumph had been ordered to land a party near Piraeus, and reported completion of the landing by signal dated 30th December 1941. However, nowhere in any of the hundreds of pages of original documents that I have seen, including the SOE’s and MI9’s own internal postwar narrative reports, is there any reference to a landing on the Greek mainland, or to a second landing. Triumph certainly had one mission that December – land the ISINGLASS party on Antiparos. The SOE record has a passing reference to the possibility of landing Atkinson on Attica (the region in which Piraeus sits), but this reference is early in the narrative, and it seems likely that SOE fitted in with the MI9 plan (it began as MI9’s mission, after all) to land on Antiparos, knowing that covert travel between Antiparos and Attica was quick and relatively safe. Here the British record goes very quiet. Triumph was lost, and the subsequent embarassment led key people in Athens to allow the story to be buried. All we have is a cryptic reference in the Staff History – “Triumph signalled that the landing had been completed on 30th December”. However, as my research in Greece wound its slow and painful way forward I discovered that the Greek record does contain the Antiparos landing, and its aftermath, in high relief, so we will move from the cold dusty files at Kew to the more colourful narrative as told to me by my diver friend and others. We now also have, by the greatest good fortune, a detailed account of what happened after the landing from Jim Craig himself, in the form of a detaiiled operational report he wrote after the war. His daugher Robyn kept a copy, which she has kindly sent on to us. Sergeant Redpath, hiding out in Antiparos with a radio set, knew of Triumph’s coming, for the Greek narrative records that signal fires were set on the Antiparos hillside to indicate to Triumph that the island was free of Italian patrols. Everyone on the island was in high spirits. The evaders, 18 mostly Australian squaddies, had been in hiding there for nearly three weeks, and on the run for several months, and were looking forward to getting home to the fleshpots of Cairo, to friends, and perhaps some leave. Antiparos’ villagers were also in high spirits (it was Christmas after all) and there is one report that all the HARLEMites had been making free with the supplies of rum landed by Thorn. Triumph, though, had urgent business, namely the landing of five thousand kilos of supplies by Folboat. In the dark, even in calm weather, this was a daunting task. You can see a Folboat in the submarine museum at Gosport, and I doubt that it would be possible to load one up with much more than 50 kilos of supplies at a time.

The Folboats would have to make about a hundred return trips the two hundred or so yards to the beach. Triumph probably had two boats, so 50 round trips per boat, and allowing for the fact that each boat would have only one rower, and with loading and unloading time, it must have been a huge challenge getting the stores up from below and ashore before dawn. The Greek narrative suggests that “the whole village” turned to in aid, and presumably the 18 evaders were also conscripted as a carrying party. I found one report that the villagers used their fishing boats, which would have speeded the business considerably. The noise and illumination would have been tremendous – forty or fifty men bumping around in the dark with torches and lanterns, tripping, swearing, and encouraging each other. It is easy to imagine Johnny Huddart biting his nails on the bridge, guns crew closed up, anxiously scanning the horizon to seaward for the shadow of an E-boat. If Triumph was caught on the surface in shallow water she would have to fight it out with her deck gun, and would probably lose. The stores were successfully landed, for Triumph signalled completion at 9pm on 30th December. Having started probably no earlier than 2100 on the 29th, she might have spent seven or eight hours unloading before thankfully slipping away to sea. She must have crept away just before dawn, dived to clear the area, then surfaced around 2000 that night to send her signal at 2121. At this point we need to focus the story on the evaders collected at Antiparos. As far as they were aware, as soon as the stores were unloaded it would be their turn to board Triumph and be carried home in relative comfort. Whether Redpath got his wires crossed, or whether he simply knew and didn’t tell them, the reality is of course that Triumph was at the start of her patrol, and was completely unable to take 18 passengers on board. We don’t have to picture the disappointment, probably bordering on anger, felt by the 18 Australians, for we have Francis Jones’ hearsay account of it in his book. To put it mildly, the Aussies were not pleased. It seems that Huddart decided not to have a debate on the beach about air consumption and food and water, but instead simply to quote a change of orders (a convenient white lie) preventing him from taking the evaders aboard. He softened the blow by telling them that he would be back in ten days to pick them up. And so Triumph left, never to be seen again. But the Antiparos story had hardly begun. After Triumph’s departure the HARLEM base contained 18 evaders, Sgt Redpath, Lt Atkinson, DIAMOND/Diamantes, Capt Jim Craig, and of course Grammatikakis. We have no record of what steps Grammatikakis took to make arrangements to get to Athens. What we do know, though, is that Grammatikakis had one girlfriend in Antiparos, and another on Paros itself, and that his Antiparos girlfriend's mother felt that he was taking unreasonable advantage of her daughter. One source I came across suggested that she rather fancied him herself. Jim Craig's report says that he had got one of the girls pregnant. One of the girls' mothers decided to make trouble for Grammatikakis by shopping him to the Italian garrison on neighbouring Paros. It seems she did this without thinking too hard about the consequences for the 21 Allied soldiers and one Greek agent hiding out on Antiparos, but shop she did, and on the afternoon of the 5th January 1942 a small Italian patrol led by an officer arrived at the Tzavellas house and demanded entry. The patrol was seen c, and Craig locked up the house and led his party into the countryside behind. The patrol hung around for an hour and then left "seeming very suspicious" in Craig's words. Craig and Atkinson had a heated conference. Craig wanted to evacuate the house and move islands. Atkinson wanted to fight it out if they came back. Eventually Craig prevailed. However, before they could act, at 2 am on the morning of the 6th January, there was a beating on the door and loud Italian voices outside. After a short delay to allow the group to prepareTzavellas first spoke to the Italians, and eventually opened the door. Tzavellas and Diamantes (DIAMOND) were taken prisoner. A few minutes later the patrol began to search the house - with Craig and Atkinson hiding nervously in an upstairs room. When the searchers came into the room Artkinson started firing - hitting the Italian officer in the chest with a bullet from his Colt 45 pistol. The wound was not immediately fatal. The searchers ran out, "helped on their way by a burst of machine gun fire from Redpath", leaving their officer on the floor. The Italian was fumbling for a hand grenade. Atkinson calmly shot him a second time, this time dead. The searchers had not gone far. A few moments later two hand grenades came flying through the window. Atkinson opened a window and jumped out, followed closely by Redpath and Craig. As they ran for the beach in the dark , with Atkinson leading by 50 yards, another grenade burst between them (this may have been what injured Atkinson's leg). Craig lost track of Atkinson at this point. Craig and Redpath briefly conferred and decided to go to the house of Baba Manoli, where the 18 or so other ranks were sleeping. The men were swiftly roused, and carrying what supplies they could were hidden on a high rock promontory by 3 am. An hour later Diamantes appeared. he had escaped from the Italians in the confusion, and returned to the Tzavellas house to rescue his radio and Atkinson's suitcase - loaded with cash, gold and a bottle of Curare poison. These had been too heavy to carry any distance so he had left them with Baba Manoli to hide. Later that morning (the 6th) the Paros garrison came to Antiparos in force. They began to comb the island for evaders, arresting Baba Manoli. The Italians searched all day, but without finding the evaders. The 7th January passed without incident. Craig sent a patrol to ask Baba Manoli's friend if he knew where the suitcases had been hidden, but the man was too frightened to cooperate. The Italians continued their search , but left the evaders undisturbed on the 8th and 9th of January. Craig describes that Triumph was due to return on the night of the 9th/10th. Other sources say the 10th January, but they might be referring to orders which allowed Triumph discretion between two dates. Given that Triumph was attacking with a torpedo on the morning of the 9th, she might have been planning to come back on the 10th (so fitting in with the standard 24 hour sanitation period before a beach landing) but Craig would not have known this. Craig set up torch signals flashing out to sea for three hours on the night of the 9th. There was no reply. He tried again on the 10th, and the 11th. The evaders' food had run out on the 8th January. By the 13th, still uncaptured, Craig's party had not eaten for nearly a week. On the afternoon of the 13th two evaders spotted a couple of sheep in a pen, went to steal them, but were spotted and fired on by an Italian patrol. This seems to have led the Italians to the vicinity of Craig's hideout, for he realised that they were surrounded. Ordering his party to split into groups of four or five and escape, Craig took Redpath, Diamantes and Lt Clarke through the Italian cordon and went in search of a boat. The search was fruitless - the garrison had removed all boats. Craig remained in hiding until the 17th January, when his party was betrayed by a local who had given them some food the night before. Capture swiftly followed. Red Cross records show that Atkinson was captured on 11 January. There is a report that Grammatikakis, having escaped the initial roundup, stole a fast launch and returned to Antiparos to try and rescue some evaders, was captured, escaped again from under the noses of his guards by diving into the sea, and then vanished. I also came across a hearsay report that the Italians discovered Triumph’s intended return date from evaders captured early in the roundup, and had anti-submarine schooners on hand ready to ambush her if she did indeed appear. Presumably signal fires were also set. Craig's account, though, confirms that none of his people were captured until the 13th at the earliest. Atkinson was captured on the 11th. There might have been another evader captured earlier who wasnt in Craig's party, but it is difficult to see how that would have happened. Craig reports that an E boat appeared on the 14th hoping to catch Triumph on the surface, but makes no mention of schooners. By 17th January all the evaders, with Atkinson, Redpath, Craig and DIAMOND, were in the bag. Disaster struck. Atkinson had taken his operation order ashore with him. Perhaps he forgot he had it in the rush to offload stores. Perhaps he just didn’t trust his memory with a large number of unfamiliar Greek names. Craig was convinced that he took it ashore deliberately Either way, when he was captured his operation order was captured with him. The Italian Second Bureau immediately recognised what they had acquired, and passed the list of names to the Gestapo in Athens for rounding up. No warning could be given, but the word must have passed quickly around the Athenian underground, for only four of the fourteen were captured by the Gestapo. However the Kanellopoulos cell was thoroughly blown, along with the credibility of the SOE and MI9 as safe comrades in arms. In the words of the SOE narrative history written after the war: “..this affair had pretty effectively knocked on the head the only party, that of Kanellopoulos, whose programme in the least degree met the wishes of the Foreign Office, or which had any chance of acting as a bridge between the (Greek) King and exiled government and the resistance.”[8] After capture Atkinson naturally tried to present himself as simply trying to help escaping allied soldiers, and therefore not a spy. His operation order sadly condemned him. After almost a year of hospitalisation (he was badly wounded in the leg, perhaps by the last grenade, we dont know), followed by movements around various Italian prisons, Atkinson ended up on trial for his life in a Military court on Patission Street in Athens on a charge of espionage and murder (the law of war did not allow an escaper to kill the enemy), in front of a panel of two Italian judges and a general. The court was held in a building only a couple of doors up from the Ioannou House, where Atkinson had hid in the summer of 1941. Efi Ioannou sneaked into the public gallery to see the trial, but was then firmly told not to go again in case Atkinson recognised her and accidentally blew her cover. It must have struck him as bizarre to be tried for his life two doors away from friends and sanctuary. Charged with Atkinson were 25 Greeks who had been implicated in the Kanellopoulos cell. Atkinson was convicted, and condemned to be killed, and was shot a month later at the Kaisariani shooting ground on 28 (or possibly the 23rd, according to Red Cross records) February 1943.[9] Reports suggest that the Italians also shot several villagers on Antiparos - presumably Tzavellas and Baba Manoli. There is a memorial to Atkinson and his fellows on Antiparos, by the chapel on Antiparos. photo courtesy of Andrew Loudon The names on the memorial are that of Atkinson, George Kapoutsos, three Patelis brothers, Spyros Tzavellas (whose house they were hiding in), Tsantanis, and Kosta Arvanitopoulos. photo courtesy of Andrew Loudon The Patelis brothers' father was also captured and died of starvation on Rhodes. Tsantanis and at least one of the Patelis brothers were killed by a German firing squad on the same day in February 1943. Another of the Patelis brothers was imprisoned rather than killed, on the grounds that he had six children to support. It is possible that the three Patelis names are the father and two sons, rather than three brothers. I have not yet been able to visit the war memorial myself, but am indebted to Andrew Loudon, who has a house on AP and kindly sent me these photos. Craig and Redpath survived the war, escaping again from an Italian prison camp. Craig won the MC twice. Grammatikakis, by now thoroughly blown, requested permission from the Allies to relocate to the Congo, where he eventually went in December 1942. To his credit, he had made every effort to rescue his comrades, and retired from British service with credit. There is a memorial to the incident and the Antiparos dead by the Tzavellas house, which still stands. One question lingers – why did none of this enter the British records (for this is the first time that the Antiparos incident has been written about anywhere in English, as far as I can find out)? There are several possibilities: - the Antiparos affair was a fairly large intelligence disaster. When the Staff History was being written, in the 1950s, it is possible that an active decision was made to suppress it in order not to destabilise Anglo Greek relations at a time when the political future of Greece was far from certain. - Triumph’s depot ship, HMS Medway, was sunk in 1942, presumably along with all the staff documents about the operation. It is possible that the Staff Historian simply didn’t know about the Antiparos incident. - All special operations were classified Most Secret. The Staff History was only classified Confidential, so if the Historian did know about the Antiparos incident he might have censored it on the grounds of classification, and used the vague reference “near Piraeus” to cover the Most Secret actual location of Antiparos. - MI9 procedures were similarly classified well into the 70s and even the 80s, against the possibility that they might need to be re-used if the Warsaw Pact ever did decide to roll over the Inner German Border.[10] - Neither SOE nor MI9 were keen to publicise what was in essence a joint disaster. Hence both of their postwar narratives skip lightly over the Antiparos incident, and the Staff Historian might therefore have missed it. We probably wont find out why Antiparos and Atkinson disappeared from the record, but at least they are now back in it.

The Mystery of Severn and Child Commando records and the CWGC both suggest that two more men died in Triumph - Corporal Clive Severn of the Northamptonshire Regiment, and Bombardier Alfred Robert Child RA. This presents a bit of a mystery. No record has come to light of what these two were doing, and Triumph's official crew list leaves them out. Both men had made recorded submarine landings in the past. So what happened? We are thinking about where we can find some more information, but meanwhile some speculation is possible. The two commandos may not have spent the whole of Triumph's patrol aboard - that would have been a waste of a precious resource. It is possible that Triumph landed them early in her patrol, and then picked them up again before Sounio (ie before 9th January). This might be an explanation for the Official History record, that agents were landed near Piraeus. We had always discounted this report as either a mistake or a cover. But what if Triumph did indeed land two more agents - Severn and Child - after the Antiparos landing operation? She might easily have done so. She would not have gone anywhere near Piraeus by sea - the waters to the north of Sounio were considered highly dangerous and too risky for a boat - but she might have landed them at her old beach of Kaki Thalassos, which is in fact quite near Piraeus as the crow flies. Severn and Child could have carried out some sabotage ops and been back to be picked up within a few days. Somewhere out there a record exists which will answer the question.

SOE and MI9 As I researched a nagging question kept coming up - why were SOE and MI9 so antagonisitic? After all, they were both on the same side, fighting the same enemy. It seemed odd to me that there should be friction, even outright infighting, between them. I have found some insights into that in Artemis Cooper's excellent book on Cairo In The War. SOE's headquarters in Cairo were at Rustum Buildings, not far from GHQ. Its politcal objectives came direct from London, but its actual operations were controlled by a Special Operations Committee in GHQ, on which SOE representatives were treated "more as prisoners in the dock than as committee members" (Sweet Escott again). Rustum was known to every Cairo taxi driver as "Secret Building". Bickham Sweet Escott worte a history of the SOE, and remarked of Cairo "Nobody ...can possibly imagine the atmosphere of jealousy, suspicion and intrigue which embittered the relations between the various secret and semi-secret departments during that summer of 1941"

The story ends Now, after the discovery of Triumph on the seabed south of Sounio, we can fill in the gaps of Triumph's last day, 9th January 1942. Here is that story

Triumph's Last Day

Triumph’s Last Day Jan 9th 1942 With the discovery of her wreck we can now make some reasonably strong deductions of what happened on Triumph’s last day. Of course, at the end of the day doubt remains, but the range of possibilities is quite small, small enough anyway to write this likely narrative of events. Triumph’s wreck is not the only evidence we have. I have spent over a decade studying Mediterranean submarine operations (there are many memoirs, reports, analyses and histories) and I’ve used this bank of knowledge to fill in the gaps. We also have the positions and headings of three torpedoes lying on the seabed near Sounio, and the positions of the minefields, as data points. What follows is a very sad story, indeed an upsetting one for the descendants of Triumph’s crew. Sadly there is no way of stepping around the sadness, but while the events are a shock, knowing what happened may also be a comfort.

If you want to skip the events before Triumph’s actual sinking and go straight to that story, then jump to “reloading the torpedo tubes”. So, let us go on. Setting the scene Perhaps the best way to start is with a map.

This shows the centre of the Aegean Sea. At top left is Cape Sounio, with its Temple of Poseidon. At bottom right is Antiparos. Here were waiting some 35 escaped soldiers from Lustreforce, the army of 50,000 men landed to protect Greece from German invasion. Almost as soon as they landed Lustreforce had found 400,000 heavily armed Germans pouring over the Greek border towards them. In the pell mell retreat that followed 10,000 men of Lustreforce were captured. Some of these escaped, and another 2,000 evaded capture and were wandering Greece looking for some way home to Egypt. Triumph’s orders were to approach the beach at Antiparos on the night of 9/10 January, pick up all the men waiting there, and sail them home to Alexandria. We know (from the Kriegsmarine War Diary, captured and translated after the war) that a submarine carried out a torpedo attack on a barge being towed by the tug Taxiarchis round Cape Sounio on 9th January 1942. We also know, from our own submarine history, that the only submarine tasked to operate in those waters that day was Triumph. It is 100% certain that it was Triumph which carried out that attack. So, we find Triumph off Cape Sounio on the morning of the 9th January, with orders to be at the beach at Antiparos at some point in the middle of the night of 9th/10th.

The Antiparos beach pickup But at what time? Probably around midnight, for three reasons. First, Triumph would need to allow herself time to make a quiet and cautious approach to the beach from the open water to the south, well after dark, creeping in on the surface on her (silent) electric motors. Her gun’s crew would be closed up ready for action. On her bridge men would be searching for the coded torchlight signal from the beach that all was safe. Triumph would have started her run in to the beach at about three miles off –within easy visual range – searching all around in case the landing had been compromised and had become a trap. At about a mile from the beach she would have reduced speed to a walking pace and brought her folding canvas canoes onto the casing until, at 200 yards from the beach, she would have stopped and lowered the canoes into the water, manned by her two embarked commandos and Lieutenant Robert Don, who served as her beach officer. Overall her approach to the beach would take the best part of an hour. It could not begin until well after the end of Marine Twilight, which was at about 1900 local time that day. We know that moonrise was at 0030 on the 10th January. Triumph would have wanted to make her approach before moonrise in case of ambush, but would have wanted to use the light of that night’s half-moon to help get the escape party into their boats on the beach and out to her – it was very hard to see a submarine on the surface in starlight so the rowers and paddlers might easily have got lost on the way. I think it is likely that Triumph’s plan was to be 200 yards off the beach by midnight, to give Robert Don and the Commandos 30 minutes to paddle ashore, marshal the escapers and to assess what other boats and helpers were available. By the time this was all done the moon would be over the horizon, and the beach party would then then get around 35 men in groups of one, two, or three out to the submarine in the light of the half-moon well before pre-dawn twilight arrived at about 0430. It would probably have taken 2-2.5 hours to ferry the escapers out to the boat, and the operation would have completed by about 0300. Below is a photo of the type of canoe used.

With her escapers aboard Triumph would then have ninety minutes of darkness in which to retire southwards, start main engines at 0330, proceed southwards at ten knots until 0430 for one more hour’s battery charge, feed the escapers a hot meal, and then dive for the first leg of the transit home. If she arrived at the beach later than midnight she might run out of night to clear the beach. If she arrived much earlier she would have to transfer the escapers in full darkness and risk men going astray.

The journey south to Antiparos With those deductions made we can work back along Triumph’s probable planned track from her patrol position off Sounio to the beach at Antiparos with some confidence. A glance at the map shows that she had four choices of track.

The northern track option passed between Kea and Kythnos. Two middle options passed between Kythnos and Serifos, and Serifos and Siphnos. The southern track option passed south of Siphnos. What the map does not show is that the three northern tracks all meet a pronounced current, a “set”, heading westwards out of the central Aegean. This is in the region of 1 knot. A modern ship or submarine would not be concerned by a slight current but Triumph’s speed when dived was only 3.5 knots, making a 1 knot current “on the nose” an issue because it cut her speed of advance by a third. The set seems to fade to zero south of Siphnos. A set matters even to a surfaced submarine. While Triumph’s two big diesels would propel her at a maximum speed of around 15 knots if pushed, pushing her was unwise (engines break if stressed and these had been in constant use for over a year) so her CO Lt Johnny Huddart would not have wanted to make more than 12 knots on the surface if possible. In the circumstances Triumph would have planned to use only one main engine for propulsion, using the other (clutched to the big electric motor) as a generator to pump charge into her batteries as she steamed south. With one engine working at a comfortable rate her speed would be about ten knots. Working back from our deduced arrival time a few miles off Antiparos at 2300 gives a track distance from there back to Sounio of 70-75 miles. The northern tracks are a few miles shorter, but have that adverse set. The southern track offered another benefit – it needed just one course change, midway between Siphnos and the island of Kimolos to the south. The southern track also has no small islets or islands to avoid along the route. Submarine navigation was hard enough, especially at night, to make a simple track without obstacles more attractive than jinking around islands in the dark without radar. I believe that Johnny Huddart chose the southern track. It is likely that Triumph planned to surface about an hour after sunset (by when the half-light of marine twilight had faded fully to black). Sunset on Jan 9th was at 1751 local time, so I think Triumph’s plan was to surface at 1830, when she would be about due west of the north end of Serifos. This would put her close enough to get a reasonable visual chart fix before firing up her diesels to sail on at ten knots while charging her batteries. On the surface with power now freely available the cook, Leading Chef Cornelius O’Brien, would be able to cook breakfast, for 1930, and lunch for 2200-2230. This passage plan would give her about nine hours dived at 3.5 knots – 31.5 miles – and 4.5 hours on the surface at ten knots – 45 miles – to arrive south of Antiparos at 2300 for her run in to the beach, with a little time in hand. By 2300 her crew would be fed, rested, and ready for five hours at Diving Stations (action stations in submarine speak) while she recovered the escapers. After leaving Antiparos she would then have a late rum ration (“Up Spirits”) as she slipped out to sea, serve dinner around the watch change from 0330 to 0430, and dive by 0500 with a full battery. To follow this plan Triumph would have to leave the area of Cape Sounio by about 1000, providing some fat in the schedule between dawn and 1000 to fit in an attack before leaving if a target presented itself. If she was delayed (for example because of a counterattack) she could catch up on her track plan by running at dived 4.5 knots for an hour or two if needed. So, we probably find Triumph lurking off Cape Sounio at periscope depth just after dawn on the 9th January at around 0700, hoping that ship traffic sailing eastwards from the port of Piraeus would pass in front of her torpedoes

Dawn off Cape Sounio It’s time for another map

Here we see a map of Triumph’s attack. At top is Cape Sounio. The white dashed line is the track of traffic passing around the cape from Piraeus. Traffic always kept very close inshore, no more than a few hundred metres off the rocks. This made it harder for an attacking submarine to develop a target picture (having to spot through the periscope against a shore background), allowed a ship to ground if hit but not sunk, gave shore-patrols a better chance of seeing the attacking periscope, and of course gave the crew less far to swim if they did sink. On the map we see Taxiarchos, the yellow oval, coming round Sounio heading east at about 6 knots. Triumph was probably lurking a couple of miles south of Sounio. This was at maximum torpedo range, but Johnny Huddart might have chosen this position to extend his reach southwards in case traffic passed further out to sea. We know she was here because of the positions of the torpedoes we have discovered on the seabed (more on that in a moment). Just south of Triumph was a line of mines. We know from postwar records that this line was 120 mines laid 60 metres apart at a depth of 12 metres, intended to sink a dived submarine. The mines were small – only 40 kgs of high explosive each – but large enough to have a good chance of either sinking a dived submarine or of forcing her to the surface within clear sight of the lookouts posted in concrete bunkers around Sounio’s coast. Two of these bunkers still exist. I visited one a few years ago, and there were at least three watch-bunkers about a mile or two apart around Sounio. The minefield was laid on 6 December 1941, just a month before. That begs an important question. Did Triumph know they were there? If an order to lay a field was transmitted by radio using an Enigma encoding machine then there was a high chance that it would be intercepted in cypher at Malta and then decoded at Bletchley Park. Malta and Alexandria therefore knew where many of the Italian minefields were in detail, and their positions were distributed in signals with a “QB” designation, some of which have ended up in the archive at Kew. (I don’t know why “QB”). The process of gaining the radio intercept, encyphering it, sending the encyphered intercept to Bletchley, waiting for Bletchley to crack it, and then disseminating the decrypt in a secure way back to the Mediterranean was necessarily slow. If the mine-lay order at the start of December was sent by radio it is quite possible, I’d say likely, that a decrypt had not reached Triumph when she left Alexandria on Boxing Day 1941. It is also quite likely that the mine-lay order was not send by radio at all. The Minelayer Barletta (which laid the field) was probably based in Piraeus at the time, and the order might well have originated just ten miles away in Athens, and been carried by a despatch rider. If Triumph did not know that the field was there from a QB signal it is likely that she saw it on her mine-detecting sonar unit when she arrived off Sounio. We know that she was fitted with an MDU because it is referred to twice in writing, once in a patrol report and the second time by inference in a letter home from my Uncle Robert Don. It was a standard fit for Batch 1 T-class submarines. We also know that it worked, because patrol reports by other T-class boats refer to its successful use in action. Triumph would have approached her “lurking” position from somewhere between east and southeast that morning at periscope depth – the same depth as the mines. An approach from that direction would have presented the mine field at an oblique angle to Triumph as an almost continuous line of contacts – hard to miss even on a 1941 model sonar. There is more circumstantial evidence. The standard operating procedure after a torpedo attack was to reverse course and sail away from the firing point – the “datum” – to open deep water as quickly as was consistent with remaining quiet and preserving battery power, to frustrate a counter-attack. The firing datum was marked by a pronounced surface disturbance – the “splash” caused by the pulses of water coming out of the torpedo tubes that launched the torpedoes. The torpedoes lying on the seabed today are on a 350 degree heading, which clearly implies that Triumph fired her torpedoes while also on that track – just west of north. That would make her normal evasion route southwards. But south from the firing datum would have taken her right across the mine-line. I believe that she knew about the mine line because she could see it on her Mine Detecting Unit, so she instead evaded westwards, parallel to the mine line. Now, back to the attack

The Taxiarchos attack Here we have four pieces of unequivocal evidence that effectively define where Triumph was when she attacked Taxiarchos. Three of these pieces are the three Mark 8 torpedoes lying on the seabed in a line west of Cape Sounio. The fourth is the torpedo detonation on the shoreline that was reported back to the Kriegsmarine. We also know that the maximum run-range of a 1941 Mark 8 torpedo in 1941 was 5,000 yards – 2.5 nautical miles. We know, finally, that the seabed torpedoes lie on a roughly 350 degree track heading. What does that add up to? A Mark 8 torpedo ran straight on the track on which it was fired – ie the heading of the firing submarine. When its fuel ran out the engine simply stopped and the torpedo sank to the seabed on that same heading. So, the track heading of the torpedoes today is the heading on which they were fired. We can extrapolate back from the course and run distance of the four torpedoes – 5,000 yards on the reciprocal course of 170 degrees – to deduce Triumph’s firing point. When we do that we find that she fired from just inside the line of mines. Because the seabed torpedoes are separated laterally by a few hundred metres we can tell that Triumph fired them “on the swing”, ie while turning either to port or starboard, but more likely to starboard as Triumph tried to “follow” Taxiarchos’ track from west to east, or left to right. An attack on the swing was known to be unreliable for aim, and it is not a surprise that all four torpedoes missed. Why did Triumph not try to close the range before firing, to increase the chance of a hit? The distances involved would have prevented her. Taxiarchos’ likely track was between the small island of Patroklos at top left and the mainland, at about six knots. She would have come into periscope sight only as she emerged from that narrow channel, and from there to the point where she turned north after passing Sounio would have taken her only 12 minutes. Triumph, sailing in from the east at 3.5 knots, would have had only that twelve minutes to take three periscope sightings, estimate Taxiarchos’ speed and course, turn north, ready her four tubes and fire. It took the torpedoes three more minutes to run to the target. There was no time to close the range. After escaping the attack Taxiarchos passed Sounio and turned north, probably now at 8 knots. Here she was already beyond 5,000 yards from Triumph and therefore out of range. To make another attack Triumph would have had to chase her from astern, with a speed advantage of just one knot. At that speed Triumph would have exhausted her battery within an hour, and been forced to surface in full daylight a few miles off Cape Sounio, which would have been tantamount to suicide. The initial attack was necessarily rushed, and it is no surprise that once the attack had failed Triumph had to let Taxiarchos go.

After the attack We know that an Italian aircraft was over the area at the time of the attack, and Triumph would have known that too because Johnny Huddart would have seen it through his periscope. What Triumph did not know was that the aircraft was unarmed. Huddart would have assumed that it was armed and should be kept at a distance, which may be another reason that she kept at extreme range from Sounio, because at periscope depth Triumph was clearly visible to a passing aircraft as a black blob in the water. After the attack the aircraft would have been able to see the firing splash, and Triumph would have assumed that it would close to attack within a couple of minutes. She would therefore have dived to over 80 feet (to gain concealment, and she had 400 feet of water to work in), speeded up a little to 4.5 knots, and high-tailed away in the opposite direction. With the mine-line to her port side that would have to be west. The standard procedure was to evade at speed for 30-60 minutes, to put some distance between the boat and her firing splash. An hour at 4.5 knots would take her comfortably past the mine-line. It is likely that she then slowed down (to conserve battery power) and sailed cautiously on searching for other mines on her sonar. Time for a third map.

With an aircraft behind her and the likelihood that the shore-patrols and/or the aircraft would summon up high speed corvettes from the north, it is likely that Triumph made a longer and faster evasion run than average. Also, a longer evasion west would take her to water in which she might, just, encounter a new target sailing south from Piraeus. Here the picture gets fuzzier. If Triumph evaded on a westerly course at 4.5 knots for thirty minutes, and then further west at 3 knots for an hour, that would take her to a little southwest of that small island of Patroklos off Cape Sounio. We can picture Johnny Huddart and Lt Alfred Peterkin, his navigating officer, crouched over the small chart table at around 1000 in the control room with a pair of brass dividers measuring off distances. The question was, turn southeast now, or wait a bit? Alfred would have pointed out that a little more westing would offer two advantages – the first was that the start of their track to Antiparos would benefit from a good position-fix using the island of Patroklos, clearly in sight 3.5 miles to their northeast, the temple of Poseidon clearly in sight to the east, and the edge of land north of Patroklos. The second was that by starting a little further west, they would have a single course to steer to hit the gap south of Siphnos, of 140 degrees, with no need to accurately time course changes along the way. 140 degrees would take them close aboard the island of Serifos about half-way, at around sunset, giving a mid-track fix from periscope depth to eliminate the errors caused by current along the track. I believe that the argument looked as strong to Johnny Huddart as it looks to me, so he decided to sail another hour or so and three miles west, past Patroklos, before turning onto a 140 degree track for Siphnos. I believe that Triumph turned onto her 140 course at about 1100 on the 9th. Sailing for 8 hours dived at 3.5 knots she would make 28 miles before surfacing west of Serifos at 1900, about 5 miles off, close enough to get a good fix.

Reloading the torpedo tubes Triumph had eight torpedo tubes – six inside her pressure hull, and one each side of the bridge but outside the pressure hull. She usually fired her internal torpedoes because these could be withdrawn from the tubes while dived for checking and maintenance during a patrol by the torpedo maintainers, which made them more reliable. There was a serious risk that a badly-maintained torpedo would suffer from a gyro failure (the gyro kept the torpedo on a straight track) and circle back after firing to hit the firing submarine. We know that accidents like this actually happened. A rogue torpedo came within six feet of sinking HMS Torbay, which only survived because she had dived immediately after firing. The men in Torbay’s control room heard her own torpedo crossing her hull a few feet over their heads. The torpedoes in the external tubes were less reliable, and were generally saved for “all out” attacks (like Triumph’s earlier attack on the cruiser Bolzano at maximum range) or for attacks after all her internal torpedoes had been fired. As far as we can tell from German records, she probably made only one other attack during her patrol from Dec 31st to Jan 9th. We don’t know for sure how many torpedoes she fired, but the probable number is two or three. On the morning of Jan 9th before the Taxiarchis attack she would therefore probably have had six torpedoes in her internal tubes, and two or three unused reloads in her torpedo stowage compartment. We know that she fired four torpedoes on Jan 9th – three are sitting on the seabed and the fourth blew up on shore. After the attack she would therefore have had two loaded tubes, four empty ones, and two or three reloads waiting to be fed into the tubes. Two of these reload torpedoes were inaccessible, sitting on racks below the deck plating of the torpedo stowage compartment, which would have had to be taken up for the reload. The deck plates can be seen in this photo of a T-class torpedo stowage compartment looking aft, with a torpedo on the right, and the arms that fold down to slide the torpedo into alignment with their tubes. This is in fact HMS Alliance, but the A-class were in most respects identical to the T’s internally.

The photo shows a pristine and empty compartment. In reality the torpedo stowage compartment on patrol was a mess of provisions, hammocks, canoes, spare gear, clothing and anything else that needed a home, for the torpedo stowage compartment was the largest compartment in the boat.

Here is the torpedo stowage compartment of one of Triumph’s sisters (Trident) in 1942 showing it in everyday use – and all the kit that would have to be cleared to get the bottom two reloads into the tubes, whose inner doors can be seen in the tube space in the middle of the picture.

Johnny Huddart would probably have concluded that there was little rush to reload. If a new target appeared on the run to the west he would not want the reloading process to get in the way of a snap shot with his last two torpedoes, so no point in getting on with that quickly. Once the run southeast began, standard operating procedures forbade any attacks en route in case they alerted the enemy to the presence of the submarine, which would make the midnight rendezvous much more dangerous. It is therefore likely that he ordered a delay to the tube reloading, securing from Diving Stations at 1030 to allow the off-watch crew to sleep before the watch change at 1200. Huddart knew that a long and stressful night awaited his crew. He also knew that men were asleep in hammocks in the torpedo stowage compartment, and would have to be disturbed for the reload. Finally, a midnight supper snack of ham sandwiches was generally served at midday, either side of the watch changeover at midday, and would distract the reloading team. I think that he and Michael Janvrin (first lieutenant, second in command and in charge of the boat’s routine) decided to delay the torpedo reload until after the watch change and the midday sandwich, and until after Triumph was sailing calmly on 140 degrees at 80 feet, safely out of sight, un-bothered by the enemy, with her crew rested and fed. If that logic is correct then the reload task would have begun at about 1215. The track plan probably looked like this.

Jump forward, work back We now need to jump forward an hour or two, and work back from what we know happened at Triumph’s end. To cut a long story short, Triumph ended up on the seabed 203 metres down, missing almost a hundred feet of her forward pressure hull, four miles northeast of the island of Ag Georgios. We know that she sank on a track of “southeast”, which is consistent with a course of 140 degrees. I have seen the video of the forward part of her wreck (Kostas has also not shared the actual video file with us in spite of several requests). This shows that the pressure hull and casing forward of the gun platform has collapsed inwards as far as about the torpedo loading hatch, and that the hatch itself, and all of the 100 feet of pressure hull forward of that, has simply disappeared, except for a shallow “scoop” of the lower fifth of the pressure hull, a bit like a marrow spoon. The damage is illustrated below:

What could have inflicted such a traumatic blow? Not a mine. Several wrecked submarines showing fatal mine damage have been photographed which we can use as comparatives. When a submarine strikes a mine the blast occurs next to its pressure hull, which is something approaching an inch thick of high quality steel. 90% of the mine’s blast energy vents away from the hull, harmlessly into the sea above, below and on the other side of the mine. Only about one tenth of the mine’s explosive power is absorbed by the submarine’s hull. This is usually enough to open a small crack in the pressure hull. The dynamics of sea pressure, flooding rate and a submarine’s inherent lack of buoyancy then quickly sink the boat. This is true even if the mine is a big one. If Triumph had simply struck a mine we would have found her more or less intact, with a crack in her fore ends. What has actually happened is that Triumph’s entire forward third has gone - disappeared. There must have been a massively larger explosion to cause that to happen. The only candidate for that much larger blast is one of her torpedoes.

Mark 8 torpedoes The Mark 8 torpedo was a powerful weapon. The torpedo itself is 18 feet long and weighs 1.5 tonnes – think a family car, squished down into a 21 inch tube. At the front of the torpedo is the warhead – 300 kgs of high explosive – which is enough to cut a ship in half. These are warheads of a similar size to Triumph’s Mark 8s:

This is a photo of a 2,500 tonne ship hit by a 300 kg torpedo warhead. Triumph was 1,600 tonnes.

If one of Triumph’s torpedoes detonated inside her we would see exactly the damage that is in fact visible. 100% of the blast would be absorbed by the pressure hull, and the weakest part of that (the upper three quadrants) would give way to and vent the blast, leaving the lower quadrant still in place. That is what we the video shows. The blast would destroy the watertight bulkhead at the aft end of the torpedo stowage compartment, which would then stop supporting the pressure hull and casing above it, and water pressure would cave the casing in downwards, which again is what the video shows. But would a torpedo detonate unintentionally? Mark 8 torpedoes were famous for their reluctance to blow up at the wrong time. While the Torpex warhead was extremely violent, it was also very stable, and could only be induced to explode by igniting a smaller explosion inside the warhead, with a more sensitive explosive. This explosive, too, was still relatively insensitive, so it too needed its own explosive detonator, a smaller and more sensitive trigger charge. So, to set off a Mark 8 one had to trigger not one but two prior explosions in exactly timed sequence, a primary charge and a secondary charge. To add even more safety, the four primary charges sat in small tubes (think brass test tubes) held on a spring outside the secondary charge, so to fire the torpedo the primary charge had to move (under spring power) into matching holes in the secondary, and then get triggered by the strikers. If the more sensitive primaries detonated by accident they would do so outside the secondary, and so not set off the warhead. I can find no example of a Mark 8 detonating at the wrong time in any wartime narrative, even those sitting on the burning deck of a cruiser after an action. Indeed, Triumph’s own Mark 8s resisted spontaneous detonation when a 250kg mine exploded ten feet away from them on the surface in the Heligoland Bight in 1939. The trigger charge in a Mark 8 was initiated by four sharp steel spikes called strikers which were held on a powerful spring in an assembly in the nose of the torpedo. The striker spring was kept back by a shear-pin and connected to a five-armed steel star sticking out of the torpedo’s nose. On hitting a target the star’s arms would push its core into the nose of the torpedo, breaking the shear-pin and releasing the firing spring. This inserted the primary charges into their slots in the secondary, where, a millisecond later, the strikers on their spring would slam home into them detonating the primaries, and then the secondary charge, and then in turn the main charge. The reason for having five spikes on the star was to make sure that the warhead detonated even if the torpedo struck its target at an oblique angle. The whole assembly was called the Pistol. Here is a schematic of the Pistol. It is possible to see two of the four strikers, poised just above their primary charges, which slot into the tubes in the secondary on the right.

While a torpedo was stored in the torpedo stowage compartment its Pistol was kept in the magazine. With the Pistol safely stowed thirty feet away from the torpedo there was no way anything could set off the secondary charge. When a torpedo was to be loaded into the tube the Pistol had to be gently screwed into the torpedo’s nose and its safety clip removed. From this point on a sufficient impact on the five steel star legs would fire the torpedo. The springs were designed so that the Pistol needed just a 5g impact to set it off. That is a low impact – about the same as a car driving into a brick wall at 5 mph – but large enough to prevent the Pistol from being triggered as the torpedo accelerated out of the tube. In 1941 Mark 8s had no “run distance” safety mechanism. The torpedo was live in the tube, and would detonate at any distance from the tube if it hit a hard enough target.

Back to Triumph The massive damage shown by the video can only be explained by the detonation of a Mark 8 warhead inside the boat. So, how did that happen? We need to return to the boat at about 1215 on 9th January. She is on her 140 degree (southeast) track at 80 feet, on electric motors at 3.5 knots. The forenoon watch (0800 to 1200) has handed over to the afternoon watch (1200-1600). Everyone on board has enjoyed a lunchtime snack of a ham sandwich and some tinned fruit cocktail. After 14 days at sea the bread is on its last legs. Chef O’Brien might bake some more that night on the way down to Antiparos. The off-watch men are heading to bunks and hammocks in their messes, but the Torpedomen have a task to do: arm and load the two or three remaining torpedoes into their tubes. By 1230 they have rigged the folding arms to slide the first reload into its tube, ignoring the moans of messmates who want to sling hammocks and catch some zeds. It is heavy work – each torpedo weighs a tonne and a half – but this is something they have done a hundred times before so they work swiftly. When the first torpedo is lined up with its tube, and has been given some basic checks (air pressure, oils topped up, depth and speed settings as ordered, fastenings all tight, screws, rudder and hydroplanes free to move) its pistol is gingerly removed from its beige green wooden box painted with yellow stencils, and is gently screwed into the nose of the torpedo. The red safety circlip is removed and returned to its box. The torpedo is now live, and the men’s movements become gentle and slow. With ropes fastened to its tail the torpedo is now heaved gently towards the open door of the tube. The pistol’s firing arms have a diameter well short of the torpedo’s 21 inches, but even so, if one of them hit anything with anything more than a gentle bump, curtains. It is safe to conclude that the firing arms did, indeed, hit something with more than a gentle bump. But what, and why? Time for another map.

The second mine-line We know, from post-war records, that on 4th December 1941 Barletta laid a second line of mines. This line, 108 large 250 kg mines, set at 12 metres deep, was laid exactly across what would become Triumph’s 140 course to Antiparos.

If my deductions so far are valid then Triumph sailed across this mine line at about 1230 on the 9th, just after Petty Officer Frank Collison removed the safety clip from a torpedo pistol and just before it was hauled safely into its tube. The obvious first question echoes the one from earlier that day – did Triumph know about the second mine line from a QB signal? I suspect not. If she had, she would have taken a different track, probably west of Agios Georgios, or perhaps close along its east coast, but her wreck position shows she did not. Also, the lines were laid within a few days of each other and were probably ordered in the same signal, so if Triumph did not know about the first mine line from an Enigma decrypt she would not have known about the second one either. If she didn’t know about the mines, did she see them on her Mine Detecting Unit? The east-west line earlier in the day was laid more densely, and Triumph approached it obliquely at the same depth as the mines, making sonar detection easier and more likely. For this second line, Triumph approached it at a depth at least 50 feet and possibly a hundred feet deeper than the mines. Triumph’s sonar dome was located at the front of her keel, deep under her hull, and it is possible that its ability to detect contacts above the pressure hull was degraded by the blanking effect of the hull. Also it is likely that the sound energy propagating from the transducer was designed to propagate in the horizontal plane, to prevent the sea surface from providing a myriad of false echoes. We know from an earlier Triumph patrol report that the Mine detecting sonar provided false echoes from the rough surface water created by a tide rip off Rhodes, when she was near the surface. It is quite possible that the Mine Detecting Unit simply did not show the mine line. Another obstacle may have prevented detection. The sea is not a uniform body of salinity and temperature. As one leaves the surface salinity changes slightly, and so does water temperature. The borders between different layers of temperature and salinity act on sound energy like mirrors – the sound energy literally bounces off the joins between two different layers, like reflecting off a mirror. The sea has a pronounced surface layer where solar energy makes the water slightly warmer (in this case, slightly less cold since it was January), where wind action mixes the water more actively, and where atmospheric evaporation increases salinity. The lower boundary of the surface layer acts as a sonar mirror (which saved the lives of many boats under depth charge attack), and it is possible that the second line of mines lay above or on the border of the surface layer, while Triumph was below the layer, with the mines hidden from her Mine Detection sonar. In any case, the number of mines for the sonar to see was small. Approaching the mine line at more or less a right angle, and with the mines laid 120 metres apart, even a fully functional sonar would see only one or two contacts ahead, which might easily be missed in the distraction of the watch handover and lunch. Another possibility is that Triumph did see the mine line, but decided to dive below it. This was a perfectly normal procedure at the time. Indeed, the only way to get into Malta, which was surrounded by multiple mine fields, was to dive below the mines and creep through. Triumph’s passage plan contained little fat for delay, and to go around Agios Giorgios to its west would have added hours to the plan and made her miss her rendezvous, and of course there was no guarantee that mines would not be found west of Ag Giorgios too. We can reasonably conclude, therefore, that Triumph crossed the mine line either unknowing, at about 80-100 feet, or fully aware, at 200 feet. The former is more likely. The most likely course of events as she crossed is that she snagged a mine mooring wire on her fore-planes. The mines were attached to a heavy sinker on the sea bed 600 feet below by a wire cable. Triumph, 30 feet wide, might easily snag one of these cables. The snagging of mine cables was mentioned often enough in the numerous memoirs of submarine captains to be predictable here. Normally the noise of a snagged cable would penetrate clearly, and terrifyingly, inside the pressure hull – a horrible metallic grating noise that could only be one thing. But not always. One memoir recalls a boat surfacing at night and seeing, to the horror of all, that she was towing a mine from her after planes and had been doing so for hours. If she snagged a mine cable, even if she knew about it, there would be little she could do. She might try going astern – not easy when dived and not guaranteed to clear a snag. She might try stopping and adjusting depth with her ballast tanks, again not easy and no guarantee of success. She might, if nothing else worked, surface to try and cut the mine free. On the surface she would become painfully visible to sharp eyes on Cape Sounio and possibly a fully alert enemy flying around overhead, but surfacing might be the lesser of two evils. But surfacing would contain another lethal risk. With a mine snagged on her fore planes, as Triumph surfaced there would be a significant risk that the mine would float on the surface just above her as she rose, and would make contact with the surfacing hull and detonate. If Johnny Huddart was fully aware of the mine, then one course of action might be open – one that was difficult and probably rarely if ever practised, but possible. Triumph would go slow astern on one screw (to take her away from the mine field in a curve), and surface while going astern. On the surface she would continue going astern, in the hope of towing the mine from her bow planes but clear of the hull, while a man cut the cable free with a hacksaw. In any event, if Huddart knew that she had snagged a mine cable he would surely have stopped the reload and ordered the pistol to be withdrawn. I think it is far more likely that Triumph did not know she had snagged a mine, because the cable was just stuck, not slipping, and making no noise. As she sailed on at 3.5 knots the mine would have been dragged down towards Triumph by the flow of water. If Triumph was at 100 feet there would be roughly 55 feet of wire between her and the mine. So, as she sailed on unknowing, the mine would have been drawn down towards her hull, making contact somewhere above the crew messes forward of her gun platform. Detonation… An almighty bang just a few feet above the heads of the men inside. A huge impulse shock to the boat, which leaps violently downwards away from the blast. As the hull cracks open and high pressure water floods in, the shock of the explosion makes the armed torpedo leap out of its loading slide and crash into the rear end of the tube. The pistol’s star-arms hit the tube door violently, pushing them back to release the strikers, and a quarter of a second later the torpedo explodes. The shock wave from the warhead detonation, moving at the speed of sound, takes only half a second to propagate through the boat. Any man standing up is thrown violently against a bulkhead, every cup, plate, spanner, becomes a violent missile flying around inside the hull. The men in the fore ends would have had only half a second in which to realise what was happening as the torpedo leapt out of their control – barely enough to register, never mind think “oh F***” – before being torn apart by the torpedo explosion. The men settling down to sleep in the three messes aft of the torpedo stowage compartment, the junior rates’ mess, the Petty Officers’ mess and the Artificers’ mess, would have been hurled violently out of their bunks stunned, if even conscious. Aft of that, the off-watch officers asleep in the wardroom and Johnny Huddart in his cupboard-sized cabin would have been thrown out of their bunks, but might have had a second in which to realise that something very large had given Triumph a death blow. With the forepart of her hull blown away a wall of water powered aft, arriving only one or two seconds after the explosion (watertight doors were rarely closed under way). The water would have swiftly reached the watchkeepers in the control room, then the signallers in their communications office, then the on-watch stokers and electrical ratings in the motor room. No more than ten seconds later the off-watch stokers in the stokers’ mess right aft would have been the last men to see the water wall arrive. With the momentum created by sailing at 3.5 knots, with only about 150 yards between the boat and the sea-bed, and sinking like a 1,600 tonne stone, Triumph’s bows would have hit the bottom about 20 seconds after the explosion, by which time everyone aboard was already, sadly, dead. And there she sat, until we found here in June of this year. One mystery remains.

The last mystery The photographs show that one of her midships external torpedoes has come part-way out of its tube. How did this happen? At sea the tube’s door was always shut, because the torpedo was armed, and its five pointed star trigger might impact a piece of debris and fire, or be triggered by a depth charge. The torpedo appears to have no pistol. It might have been ripped off by a fishing net, but when you look back at the schematic you can see that the firing arms are really solid, and screwed tightly into a solid torpedo nose. Another scenario is possible, and I think more likely. The external tubes had a hard life – always wet, buffeted by waves on the surface, and under pressure when dived. They had been in continuous service for over a year. If the hydraulic system for opening and closing their doors had malfunctioned the door might have jammed open at some point in the patrol. If that happened (which is quite likely) then it would become essential to remove the pistol to prevent an accidental detonation, either from a random impact or during a depth charge attack. Removal would be easy, surfaced at night, leaving an inert torpedo in the tube open to sea but not a danger. Then, as Triumph collided with the sea bed at 3.5 knots, pointing down at an angle of about 45 degrees, the momentum of the 1.5 tonne torpedo might easily make it slid it a few feet out of its tube, leaving it for us to find, pistol-less, 80 years later.

* * * * *