Triumph and the Ts - a history

Triumph and the Ts - a historyThe book of the Triumph story is now available on Amazon. The book tells the story of the boat and her crew over the whole of 1941, and of how she became involved in the fall of Greece, the work of SOE, MI9 and escaping POWs afterwards. The book also follows the stories of three of her key agents, the New Zealander Jim Craig, John Atkinson of the RASC and the Greek smuggler and resistance member Harry Grammatikakis. We follow them into Greece, then into hiding in Athens, and finally into Triumph’s fated last patrol. The mystery of Triumph’s disappearance is answered.

Buy your copy on Amazon here

In the mid 1930s the Royal Navy had a problem. Submarines built after WW1 were due to be retired under disarmament treaties. The same treaties mandated a size limit of 2,000 tons surfaced. The Conservative Cabinet wanted to abandon submarines altogether, but operationally there was a need to have a boat capable of operating against the Japanese fleet in the vast waters of the Far East. Part of the Admiralty’s answer was to mandate a flotilla of 20 1,000 tonne long range patrol submarines.

Operationally, there were challenges too. A submarine aims its torpedoes by taking sights of its target through its periscope, and attempting to calculate the target’s course and speed from perhaps three quick looks. With this information a salvo of four torpedoes, spread like the shot from a shotgun, gave a reasonable chance of making a hit (one hit was usually enough). But, to make this maths work, the submarine had to be very close to its target – less than 2000 yards was good.

Practice showed that it was becoming harder and harder for a slow dived submarine to penetrate the destroyer screen around a large target without being detected and sunk. So, firing from a longer range, of up to 7000 yards, meant that the firing solution of target course and speed would be less accurate. The answer to this was to fire more torpedoes in the salvo. One early suggestion was for the new attack submarine to have six tubes internal to her hull (and thus reloadable) and twelve fitted on her deck, giving a theoretical salvo of 18.

During 1934 discussions came down to a design of roughly 1,200 tons displacement, fitted with six internal tubes and four external, facing forward, to give a salvo of ten shots. With a hundred tons of fuel this new design would be able to carry out a patrol of 6,000 miles, giving an operational endurance of well above the 30-40 days required. A year of debate and specification followed, ending in 1935 with agreement on a slightly smaller boat, at 1,100 tons displacement (the extra 100 tonnes was for fuel and batteries, to give enough electric power to remain submerged in the long northern daylight hours), and armed with six internal and four external (single shot) tubes. One compromise, to bring the size down to 1,100 tonnes, was that operational range was lower, at 4,500 miles, reducing the maximum practical patrol period to about 30 days (less if the patrol area was a long way from base). This design was designated the “T” class (since the experimental Holland boats all British submarines have always had a single letter class designation, starting with the “A”s, and currently at “V”s with the 16,000 tonne SSBNs in service today). 34 Ts were to be ordered initially, the first being Triton in 1935, and the second being Triumph, at a cost of £305,038. It is interesting to note that a full load of torpedoes added some £50,000 to a boat’s price. Triumph was built by Vickers Armstrong. This is a video of her launch...

By the end of the war the T class programme had expanded to 53 boats.

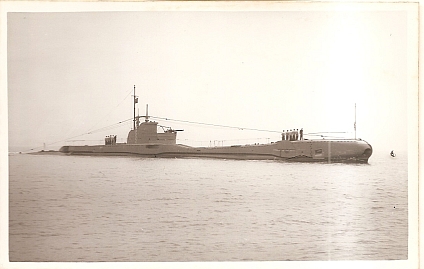

The Ts were graceful boats. Forward the two external tubes were housed in a sweeping bulbous bow, and two more amidships in bulges next to the conning tower. Though handsome, these bulbous bows were found to reduce surface speed by up to a quarter in heavy seas, so when Triumph had her bows blown off by a mine in 1939 she was repaired without the two external tubes, and sailed thereafter with a very slim bow profile (which is clearly visible in our photograph of her).

The first three boats had high open bridges on top of their conning towers. Experience showed that these were very wet and windy, so Triumph and her later sisters were fitted with partially covered bridges (called “cab bridges”) to give watchkeepers some shelter from the elements.

Until 1942 all RN submarines were riveted rather than welded. Welding was regarded with suspicion, and in any case the yards did not have enough skilled welders to do the work. With riveted hulls and frames Triumph had a safe diving depth of 300 feet (though later tests showed that these calculations were pessimistic, and could be extended by 10%). Some boats reported surviving dives to 400 feet, and even 450 feet was touched by sterns and bows when dives were made at substantial angles, but Triumph’s maximum depth was certainly less than 400 feet. T’s dived quickly, going from a “trimmed down” state to dived in less than 30 seconds.

Triumph was powered by two Vickers diesels at 1250 HP each, and on the surface could just about touch 14.5 knots in good conditions. Her usual surfaced speed was 11 knots. Though her electric motors could in theory push her up to 9 knots when dived, at this speed she would run out of power in less than an hour, so she rarely exceeded 3 knots.

Triumph’s design complement was 53, but by the time she was lost this had increased to 57, in order to give key personnel additional watchkeepers to allow them to rest. However the Ts only had 48 bunks, and under way even some of these were unusable, requiring crew to share bunks (“hot-bunking”).

Here is a video of her sister Trespasser operating after the war. Very little would have changed...www.britishpathe.com/video/submarine-1/query/submarine

Triumph carried six Mk VIII torpedoes in her internal tubes, with six reloads in the compartment astern of the tubes. Each torpedo weighed 1.5 tonnes, and when fired was replaced by 1.5 tonnes of water to prevent the boat from arriving suddenly on the surface in view of the enemy. The warheads of Mk VIIIs were very stable. Triumph’s torpedoes were within feet of the explosion of a large German mine in 1939, but none of them detonated. Other boats had similar experiences, and there is no record of a T boat experiencing a sympathetic detonation of one of its torpedoes.

In order to hit a target Triumph had to predict the future position of the target and fire her torpedoes into that position. At a firing range of, say, 4,000 yards the torpedo would run for 160 seconds, during which a fast warship target moving at 20 knots would have moved approximately a mile. Solution of this complex geometrical problem rested on the CO taking a few very accurate sights of the target’s course, speed and range, and inputting these to a mechanical analogue calculator (the Fruit Machine) which would use complex engineering to show what angle the torpedo should be fired at. The firing solution was not a continuous output – each input produced a fixed solution and the boat had to be manoeuvred to fit that solution, with the torpedo being fired as the target came onto the firing line on the lens. Errors were compensated for by firing multiple torpedoes at set intervals – roughly ten to fifteen seconds – governed by the length and speed of the target. It was easy to miss, and accuracy was very much the personal challenge of the CO, who was the only person actually to see the target.

Torpedoes, carrying 365kg of high explosive, were designed to sink large ships. Given the need to fire a salvo in each attack it was accepted that a boat might only make three or four torpedo attacks on a patrol. So what to do about smaller targets? Ts were fitted with a 4 inch deck gun to engage targets which were (a) unescorted and (b) too small to warrant a torpedo salvo. The deck gun could also be used to bombard shore targets (many trains were killed in this way), and in extremis as a self defence weapon, though the best defence was always a swift dive.

The tactic was to scope out the target while dived (and make sure that there were no escorts or aircraft around) and then to surface rapidly, with the gun’s crew climbing a dedicated ladder to the gun platform. In order to be able to bring the gun into action quickly, while the boat was still surfacing, the gun was placed relatively high on the casing, on a rotating platform just forward of the bridge. A well practiced team could activate the gun and fire six aimed shots within a minute of the boat first breaking surface.

For a great diesel boat website have a look here www.rnsubs.co.uk/Dits/Articles/ds48.php

This youtube video posted by David Bober www.youtube.com/watch?v=hODdzbvrDQk shows clips from the movie Close Quarters - featuring a T boat on patrol.